The Anatomy of Peace is a deeply insightful book about how our default thinking processes lead us to conflict with others and reveals a path towards peace.

Our relationships with others form the foundation of our reality. Sadly, we are habituated on twisting and distorting our “reality” of these relationships to protect our ego. The net result is that we are the authors of much of the conflict in out lives.

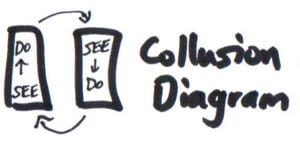

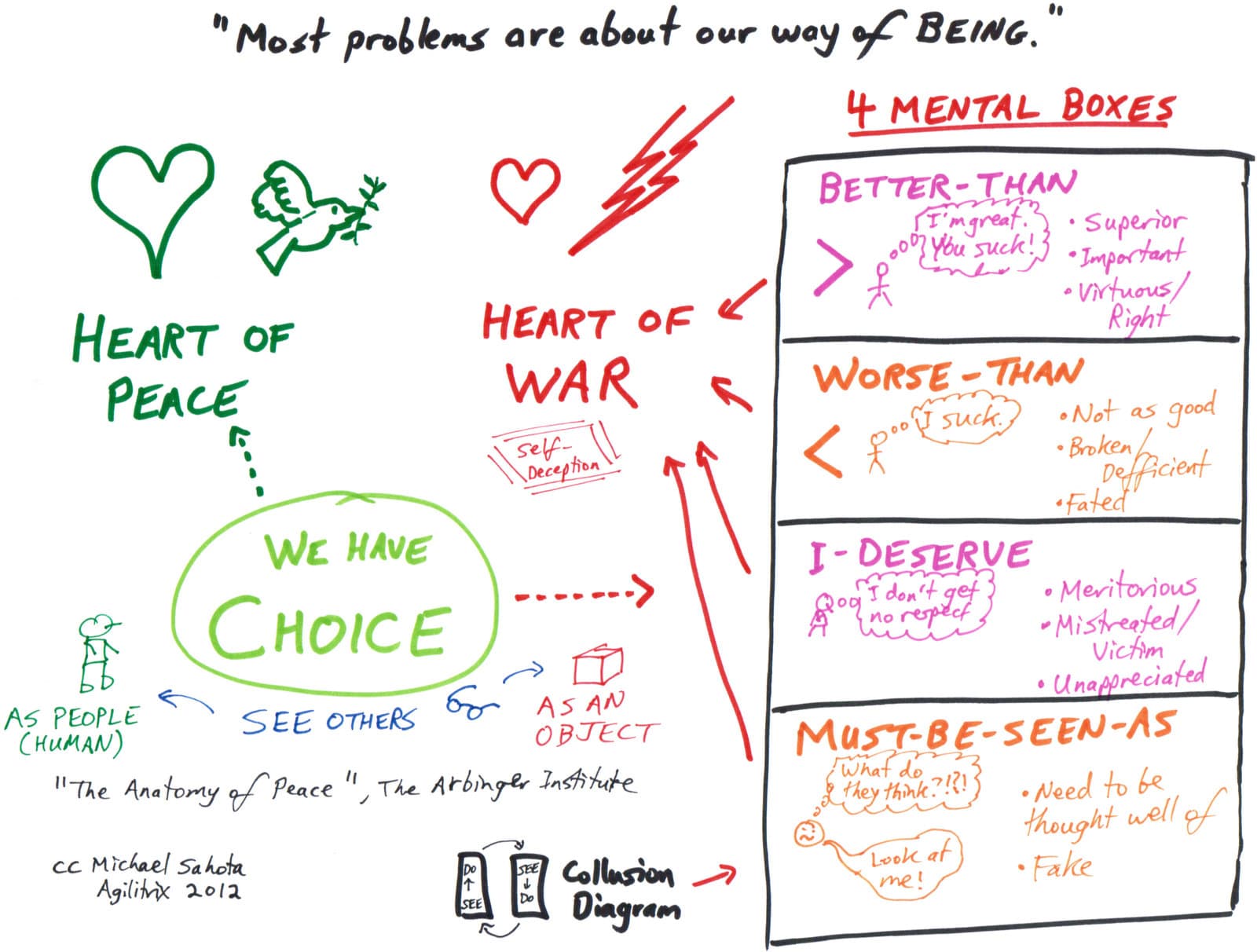

Consider the visual summary below that illustrates a model for understanding communication and understanding reality.

Every relationship can either be approached with either a heart of peace or a heart of war.

When we have a heart of peace, we see the other person or group as a unique and valuable human being. We see them as a person – we recognize their humanity. We acknowledge that they have their own consciousness and life.

When we have a heart of war, we see others as objects, as things. We no longer value or treat them as human. Of course, we don’t intentionally choose to do this. This happens inadvertently when our mind protects our feelings. Psychologically, we create a self-deception that comforts us in the face of emotional challenge.

Most of the problems in the world are related with our way of being with others (peace or war).

Four Forms of Self-Deception

The book describes four forms of self-deception. With each one we create a mental box that we trap ourselves in. Each box colours what we see and experience. The box provides psychological safety, so it takes courage to examine it and rebuild relationships in our lives.

Better Than

When people are in a better-than mental box, they see themselves as superior to others. They think they are more important and that their cause or arguement is the most virtuous one. They look down on others as inferior and flawed. This has been my main “go-to” box for most of my life.

Worse Than

People in a worse-than box, see themselves as flawed and inferior to others. They see themselves as deficient and fated to have negative outcomes. They see the world as a hard and difficult place with others being the lucky ones.

I Deserve

This box is about feeling that one is hard done by life. People feel like they are a victim and that no on recognizes they value and contribution. I think of Rodey Dangerfield’s comic tag line “I don’t get no respect.”

Must Be Seen As

People in this box crave attention and feel like they are being watched and judged. They need to be thought well of and will work hard to fit in. Extreme clinical expression of this is Histrionic personality disorder. This is my second go-to box for twisting reality to feel good about myself.

The self-deceptions we chose depend on the person we are with and the context. Over the course of a week, we may at some point fall into each of these mental boxes. From a learning and growth perspective it is valuable to note what boxes we commonly go to across people and contexts.

Shame

An interesting question is how this work relates to Brene Brown’s research on shame. Since a key element of shame is that people feel like they are unworthy of love and belonging, this would fall right in the worse-than box. That’s just the start, in my own experience, shame also activates other boxes to mitigate the pain.

We need to be in a Heart of Peace to express empathy or compassion for another person. To the extent that we are trapped in a box we will not be available to express empathy to another person.

How We Collude with Others

It turns out that “normal” human behaviour can trigger a downward spiral of negativity where two people collude to stay in their boxes. It starts when one person, A, sees B do something and interprets it from their box. A passes judgement on B and then acts in kind. B sees A’s action and interprets it from their box. They think of A as an object and act in a way that treats A as an object. And the cycle continues and feeds on itself. At any time A or B can break the cycle by going to a heart of peace and seeing the other as a valuable human being. A good way to break the cycle is by noticing what box you are in and then using your imagination and desire for a positive outcome to make a different choice of action.

What to do when you get stuck

- Notice when you fall into one of these mental boxes (or traps!)

- Be kind to yourself. All of us have these problems and you are working on it. Good job.

- Go to a mental place where you are more resourceful. This could be a walk outside, stretching, meditating, listening to music, etc.

- See how your thoughts and behaviours contributed to the situation.

- Seek to see the humanity in the other person – imagine why a responsible, resourceful human being would behave that way.

- Start the conversation again, but this time from your heart – think about what you really want in the relationship. See: Crucial Conversations.

Acknowledgements

I would like to than Jukka Lindström for introducing me to the book – he said it was one of the most influential books he has read in the last few years. I have to agree. I would also like to thank and acknowledge the Arbinger Institute for collaboratively creating such a wonderful book.